Pastport

A celebration of some of Logan Square's historic watering holes.

Click each logo above to jump to the corresponding bar's history!

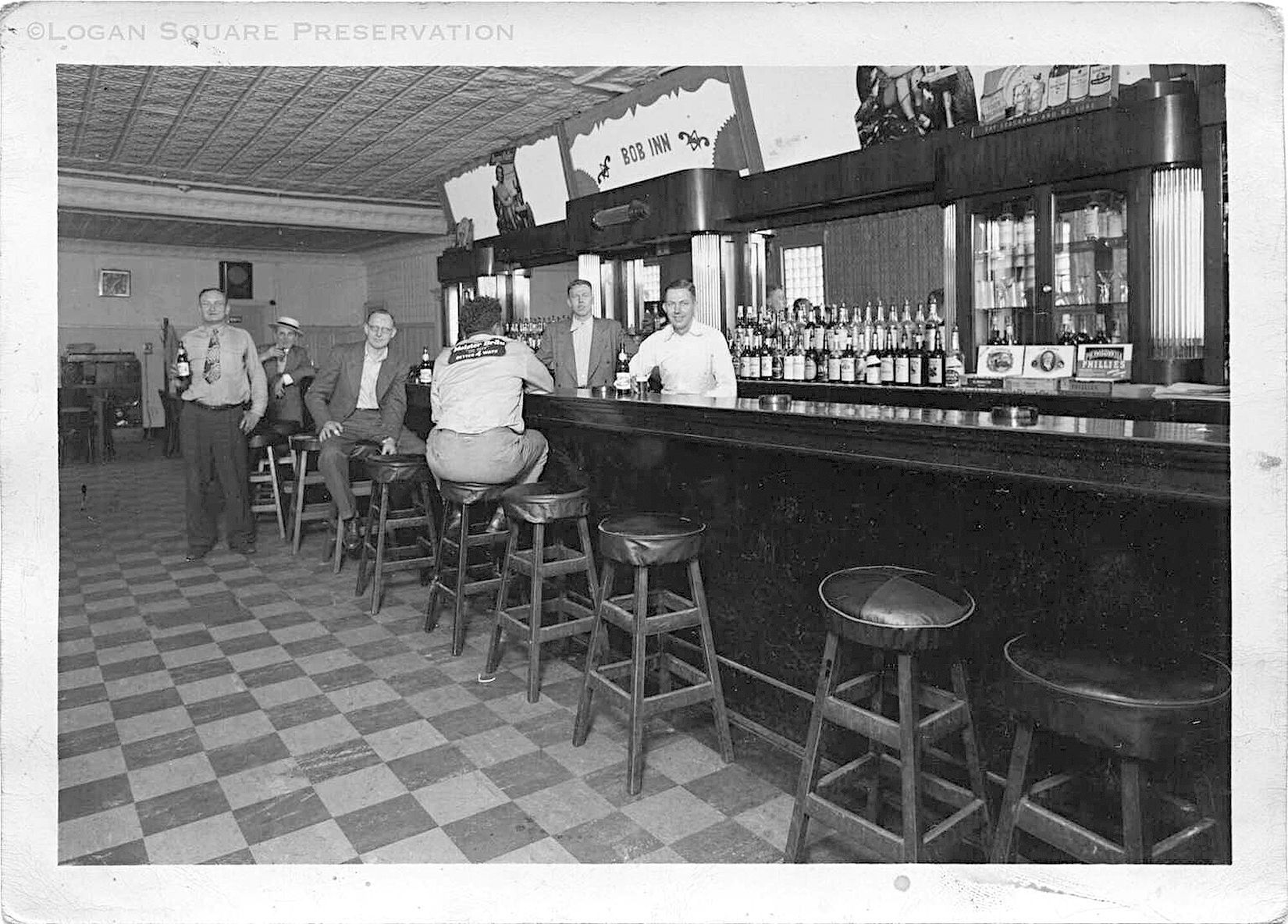

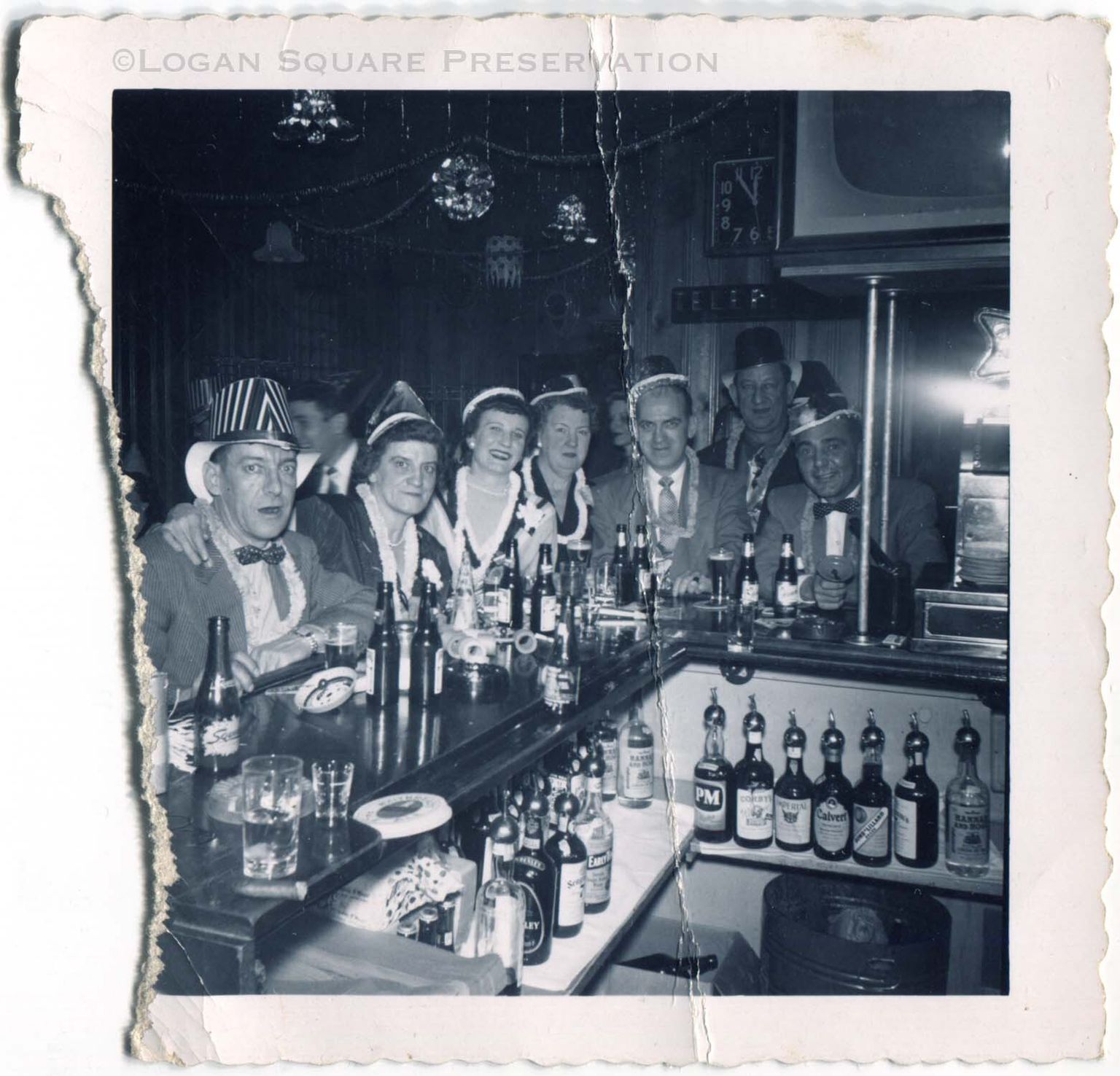

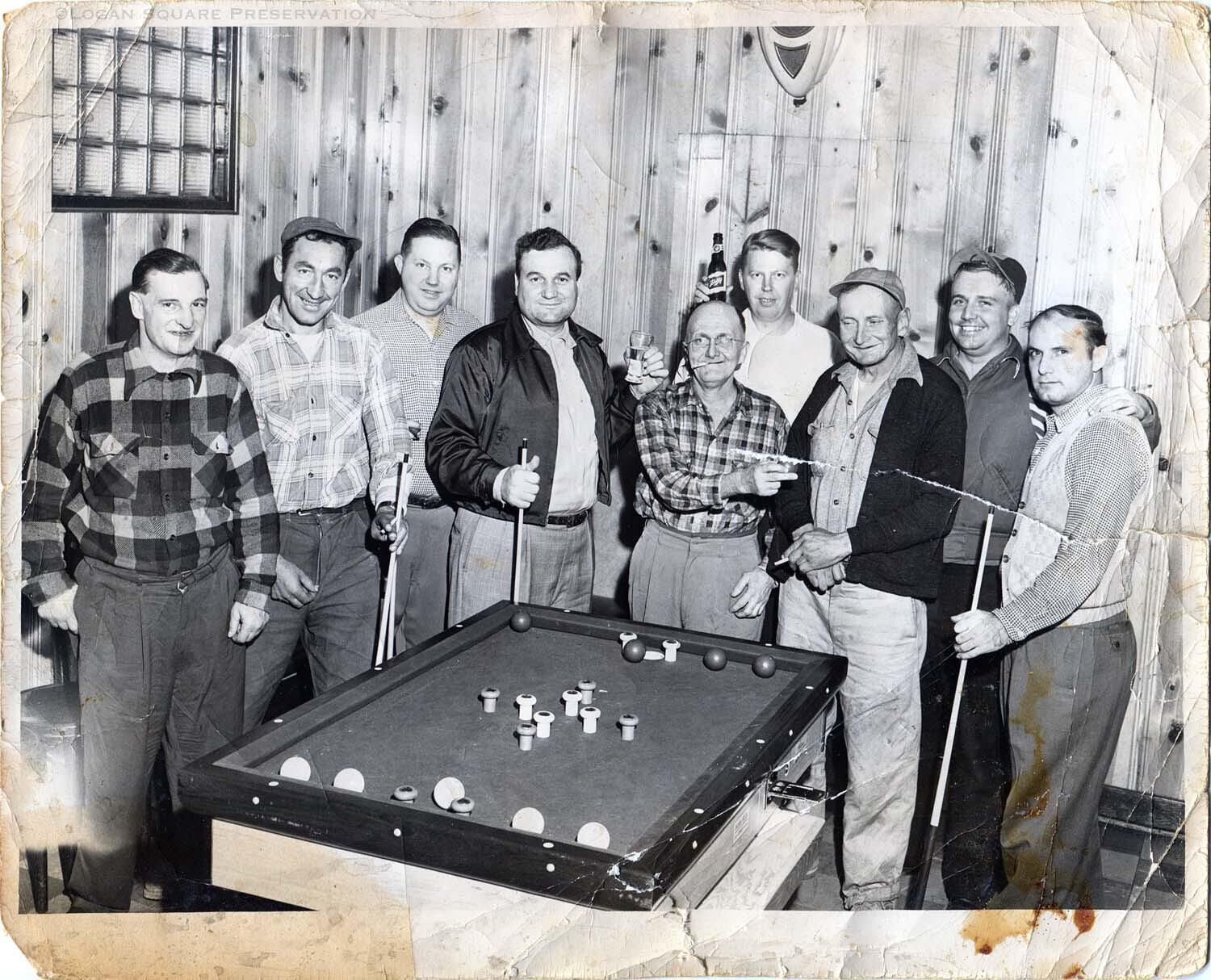

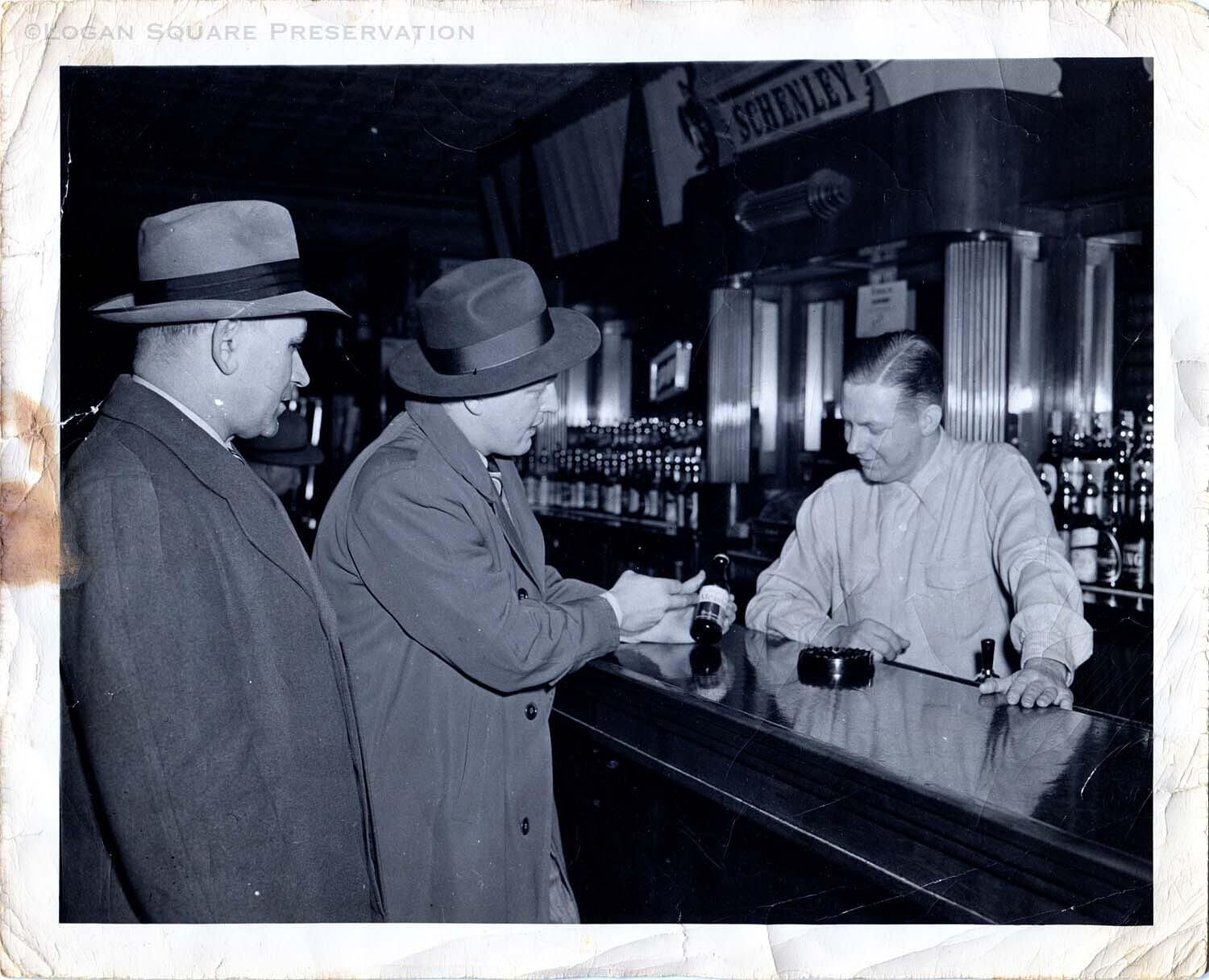

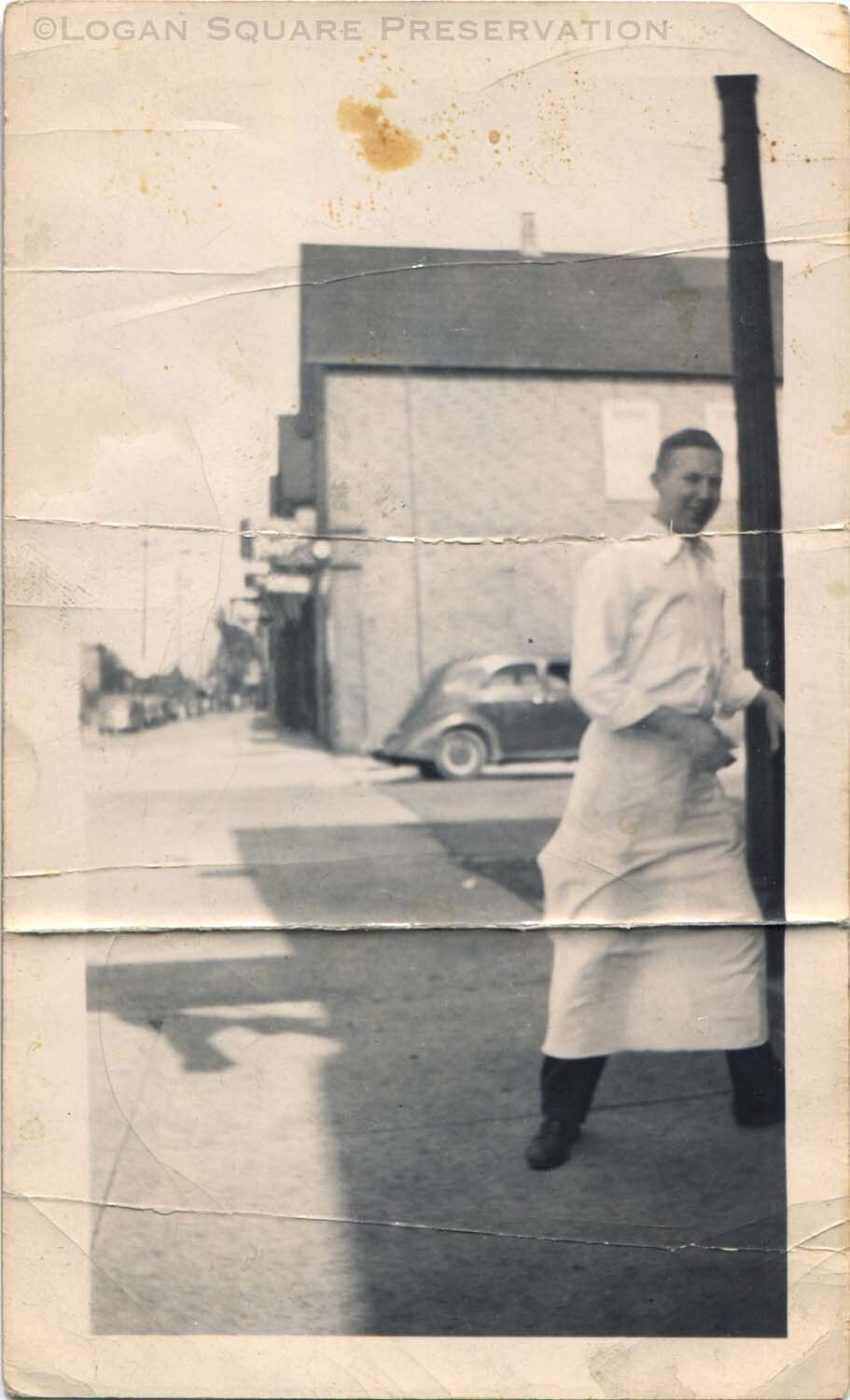

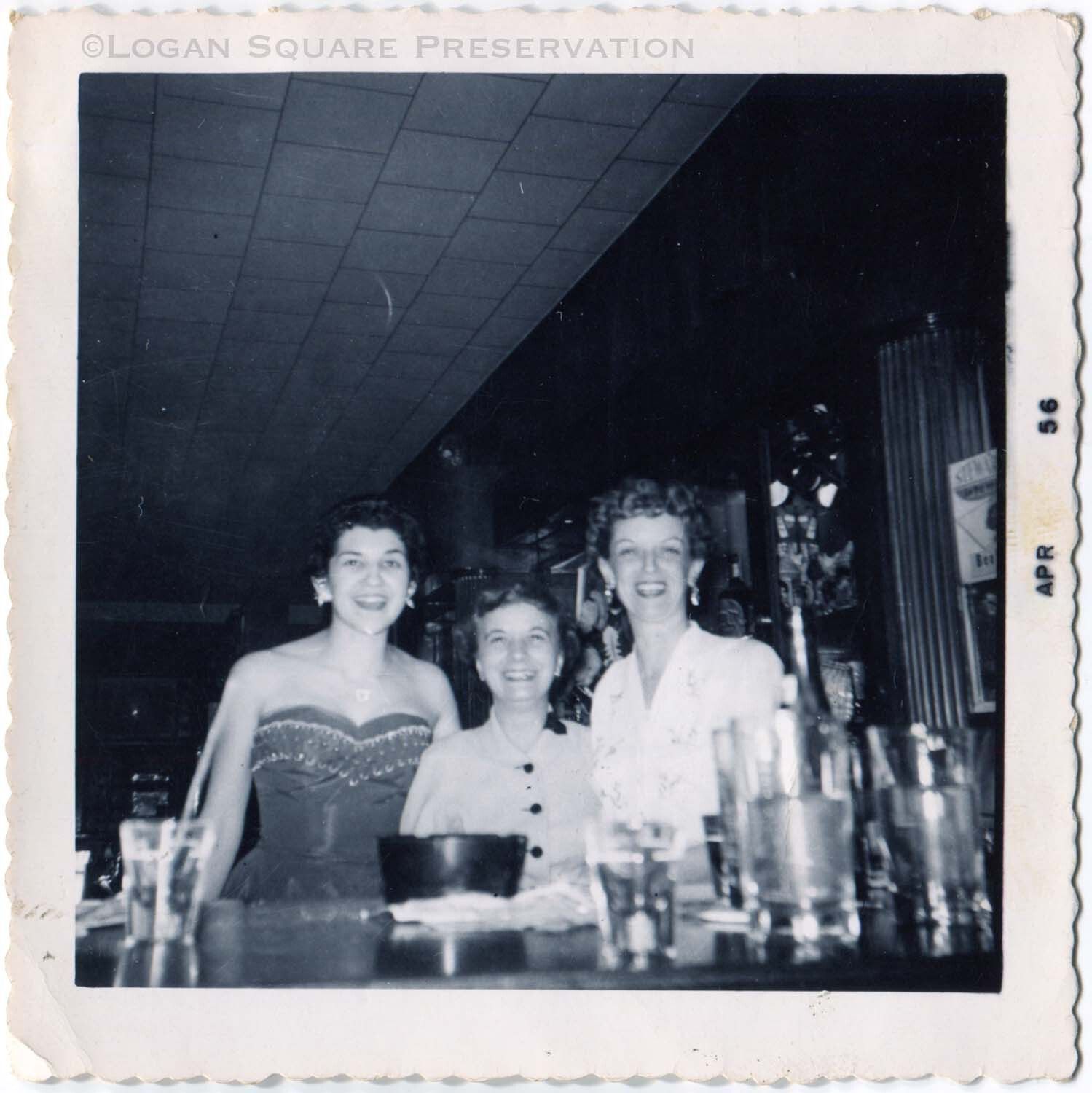

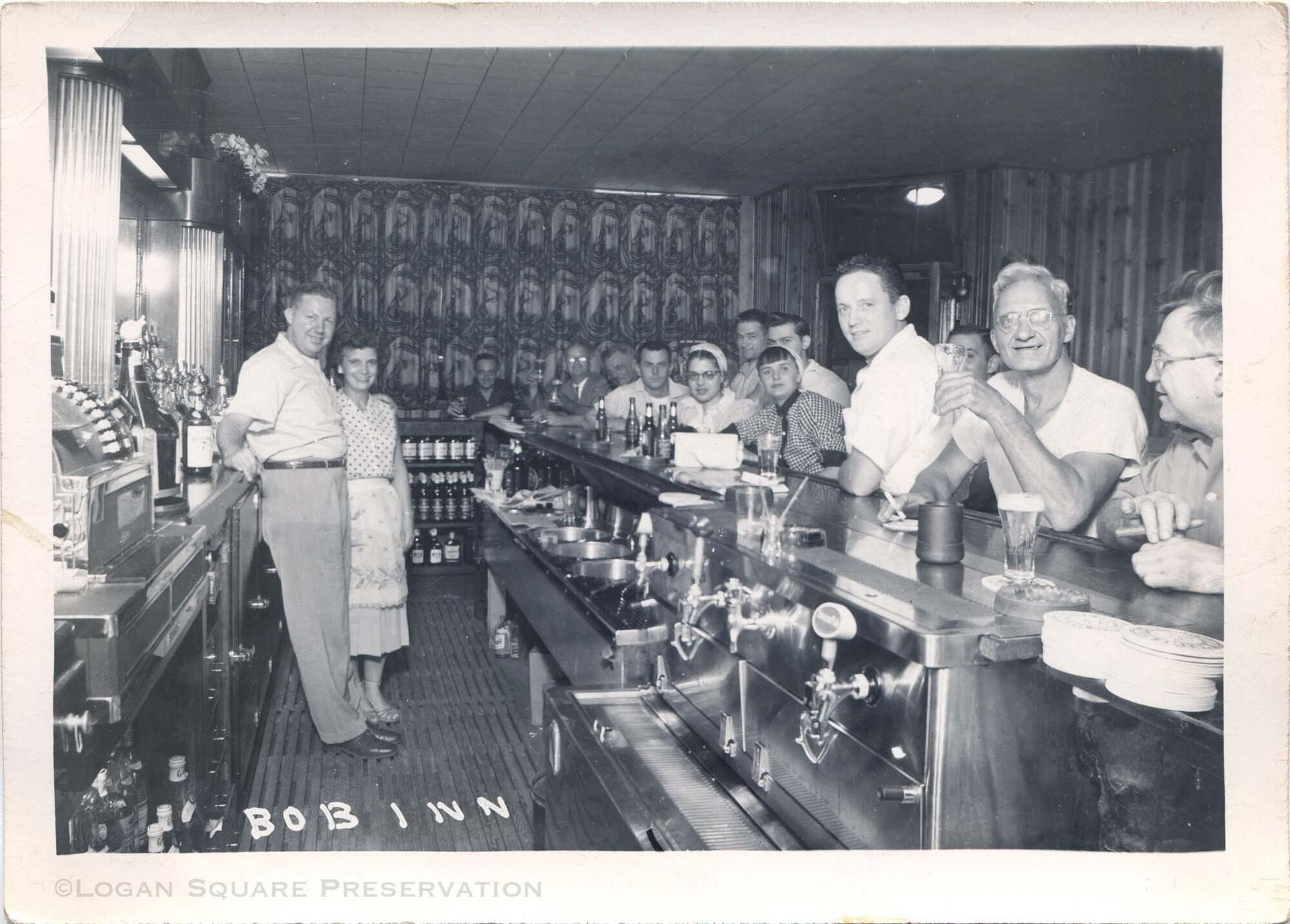

Bob Inn

2609 W Fullerton Ave, Chicago, IL 60647

More than just a beloved neighborhood dive, The Bob Inn is among the oldest family-owned establishments in the city. The first tavern opened shortly after it was built in 1889, and it remained so ever since – with a brief stint as a soda parlor and billiard hall during Prohibitions. When it went up for sale near the end of WWII, local munitions worker Bob Hanson knew he’d found a good investment – for his older brother Harold’s Navy pay. Harold sent his savings and by the time his tour ended in 1945, the bar was up and running under his brother’s name. They would take turns keeping it open a staggering 7 days a week from 7 a.m. to 2 a.m. Harold and his wife Cecelia (nicknamed “Terry”) moved into the two-bedroom apartment above with their young son, Terry, who sadly passed a few months ago. Four more children were born there— Betty, Mariann, Linda (the family tomboy always called DeDe), and the youngest, Jimmy.

In 1961, when the next door candy store moved two doors down, the brothers opened the Bob Inn Grill with Harold at its helm. It operated 24 hours a day, offering burgers and dogs, including a “Goethe burger” (then pronounced “Gay-thee”) for the kids at the nearby school. The Hanson kids — all St. John Berchmans students — bolted down their own lunches to help serve what Mariann remembers as the “double line of kids” at the grill at lunchtime. In 1964, the brothers bought both buildings, working long hours at the twin businesses and hiring an ever-changing cast of “swampers” — locals who would mop up or do other jobs in exchange for a few bucks and a few drinks.

The Hanson kids also worked there, sorting the week’s cast-off bottles for pickup by the beer trucks. But they played too: In the bar’s backroom, they stacked beer crates to make forts and put on shows. They bounced balls off the building in endless games of “ledge-ball” and scaled the fence to play at Goethe Park until their feet were “too big to fit in the links.” The Bob Inn grew up, too. Its tin was covered by drop ceilings and knotty pine paneling – a homey look appreciated by a blue-collar crowd who worked in the five nearby factories. They could get rowdy; the original neon window sign was broken repeatedly — sometimes by hijinks in the bar, and once when someone fighting in the street threw a muffler through the plate-glass window. But patrons loved the Bob Inn. It was a place to cash your checks, borrow a few bucks, talk Harold into a free burger, hold a fundraiser or a party.

The bar sponsored softball teams and rented rooms upstairs to folks few others would rent to. When regulars went on vacation, they sent the bar postcards: “Miss you guys,” they would write, “Yosemite is great, but wish we were there with you!” Harold saved every one. The bar became famous for its annual picnics and bus rides to sporting events. Harold was an intransigent Sox follower; wife Terry was a diehard Cubs fan. The kids took sides, too: the sisters, Cubs, Jimmy, Sox. As the Hanson kids hit their teens, the sisters got jobs at the dry cleaner and other local businesses because “Dad wouldn’t pay us.” When he was younger, Jimmy made pocket money going from bar to bar with a shoeshine kit. “There were 18 bars just between Western and California,” he recalls.

When his dad put him to work, Jimmy demanded a salary of $25 a week. He would earn every penny. One day on his way to school, Jimmy remembers glancing behind the bar and seeing one of the “swampers” lying there. “Dad!” he called up the stairs. “I think Harry’s dead.” When Bob announced he was retiring in 1978, Terry was off at college; the girls had married and moved out. Harold told Jimmy, then 23, to quit his night job loading trucks at the railroad yard for $9 an hour — “good 1970s money” — to run the bar for $2 an hour. Jimmy complied. He knew it was no use fighting the family’s business vortex. The bar “got really busy when Jimmy’s friends started showing up,” Mariann recalls. It was Jimmy who added the shamrockbedecked insignia above the door, recycling an old Budweiser sign. The worn back bar was swapped out in pieces, often from the detritus of other taverns. In 1983, Jimmy married Ann, a neighborhood girl who cut hair in a nearby barbershop.

“Her sister used to come in here,” Jimmy says, implying Ann was too young (or too nice) to be a regular. But once married, Ann found herself working there, too — and going head-to-head with Harold for being, as most agreed, “too easy” on the customers. He would let them linger at the grill over a single bottomless cup of coffee, read the newspapers on sale and put them back. When Ann tried to raise the prices on the pegboard menu, Harold would wait until she left and change them back. The grill was a beloved fixture in the neighborhood until it closed when Harold died in 2002 at the age of 86.

For 30 years, Bob and Harold ran the bar, each taking one Sunday off every other week. Now, Ann still opens the bar every day for its first shift. She and Jimmy live in Jimmy’s childhood home, where they raised two daughters, Jami and Mandi. That makes Jimmy something of a neighborhood oracle — point to any storefront on Fullerton, and he can tell you what used to be there. And he can be consulted most Sunday mornings, as he sits at the bar playing Cribbage with the regulars — the same way his dad did — for hours. After a tough couple of years with the pandemic and some health issues, Jimmy is content, though he says he wishes his kids would “take over

right now.” Ann seems doubtful. “They have good jobs,”she says, though she admits that from time to time, you’ll find them (where else?) working behind the bar. Family tradition can be a powerful thing.

Green Eye Lounge

2403 W Homer St, Chicago, IL 60647

Look around -- there are ghosts everywhere: the patio below the Blueline stairs was once a hotdog stand (first the Snappy Snack Shop, then Diane's Hot Dogs); the pinball/party room was Frank’s Barber Shop (the sign is still hanging on the wall). The bar itself, with its classic lightbox Old Style sign, was the “West-Ho Tap” (for Western at Homer streets). Back in the day, it was a gritty 7 a.m. shot-and-a-beer spot with a drop ceiling to save heating costs, and a busted up Brunswick barback.

The Western train stop first opened in 1895. Just a year later, the building that now houses Green Eye went up with a bar in front and a meat market in back. The now-departed hotdog stand was added in 1953; the barbershop, run by two Italian brothers, was already there. Two years later the bar, likely already with the West-Ho-Tap moniker, made headlines when a disgruntled customer shot the bartender in the foot.

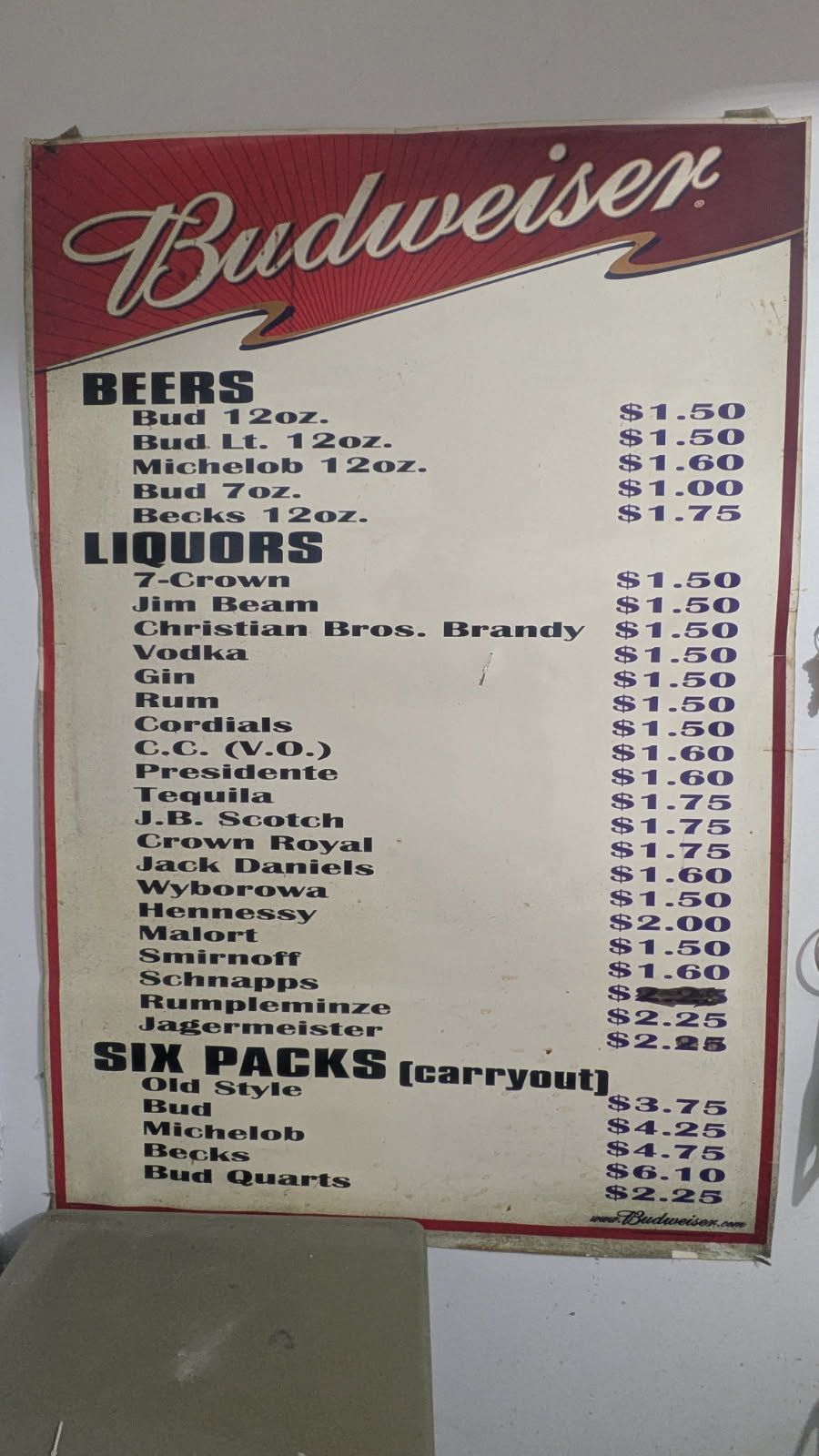

The current owners bought the place in 2003 and salvaged parts of another classic Brunswick to restore the bar to its current glory. It was christened the “Green Eye” as a nod to its commuter stop location: GreenEye being train lingo telling the conductor that the racks ahead are “clear to proceed.” They kept the old drink menu: $1.50 for a shot of Beam (and darn near everything else) $1.65 for a shot of Jack Daniels. And, if you look at the East exterior wall in the beer garden, you’ll see the brick is uneven. That’s because it was interior brick from another building that once stood there (also why there are no windows on that side). That building was torn down when they widened Western Avenue.

Whirlaway Lounge

3224 W Fullerton Ave, Chicago, IL 60647

Now forgotten by all but diehard racing aficionados, a thoroughbred called Whirlaway, renowned for his unexpected wins and erratic losses, was briefly the most famous horse in America — and the inspiration for one of Logan Square’s oldest and most beloved bars.

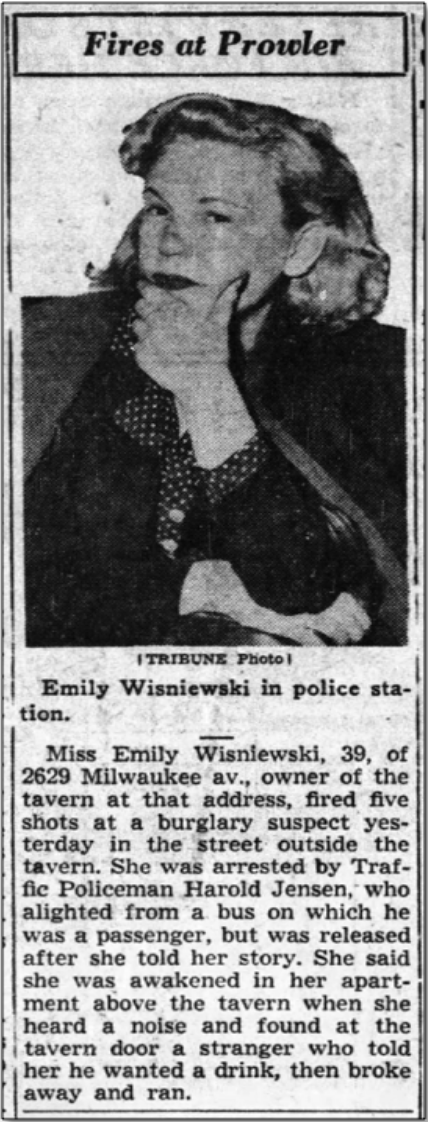

Whirlaway’s first win was in suburban Chicago at Lincoln Fields (now Balmoral Park) in 1940; the following year he won the Triple Crown. Shortly thereafter, the Whirlaway Cocktail Lounge opened at 2629 N. Milwaukee Ave. storefront with an owner’s quarters above. Local lore claims it was a winning bet on Whirlaway that staked the former tire store’s retrofit as a bar. But the owner may have placed one bet too many on the fickle colt: The lounge was for rent in 1946 and had a new owner by 1952. Emily Wisniewski, an immigrant from Grodno, Poland, married and naturalized in 1936, but her husband seems to have been long gone by the time the Chicago Tribune ran a story on “Miss” Emily Wisniewski. The 39-year-old Whirlaway owner had confronted a would-be burglar and chased him down the street, firing her gun five times. The Dec. 7, 1953 headline: “Fires at Prowler” tops a carefully posed photo of Emily giving the camera the side-eye. Police declined to detain her, finding her response perfectly reasonable for the time — and the neighborhood.

Years later, on Dec 29, 1967, Emily found her saloon threatened by a force bullets couldn’t stop. The City of Chicago condemned a block of buildings along Milwaukee including the Whirlaway to make way for Blue Line construction. With just weeks to go before the wrecking ball, Emily turned her attention to a little bar that was for sale at 3224 Fullerton Ave.

Said to have once been owned by a local gambler who went by the Runyon-esque moniker “Broadway Jones,” it featured an owner’s quarters at the back, two apartments above, and a terracotta storefront. It apparently had a legacy in liquor: a 1909 story tells of a “bloody dirk [dagger] wrapped in human hair” found behind a liquor store at that address, but no victim was found. Despite its slightly sordid history, Emily bought the place and rechristened it with the Whirlaway name she’d paid for — adding the Polish word for tavern, “Karczma,” to its new awning. She continued to run the bar with an iron hand until 1980, when, at the age of 70, she decided to retire (she would live another 20 years).

Maria Jaimes and her husband, Sergio, naturalized immigrants from Mexico, approached her with an offer, and Wisniewski accepted. Maria remembers Emily as a feisty owner — she would use the backyard hose to disperse patrons when they got out of hand or she had simply had enough of them. Maria wondered how any one woman could run such a rough-and-tumble place, not realizing she would one day have to do just that after her beloved husband passed away in 2009.

Since then, with the help of her son, Sergio Jr., Maria has become the den mother to a (somewhat) less rowdy clientele. With her encouragement, they don full Blackhawks gear for every game, dress up for Halloween, and occupy the stools on nearly any sports night. As the neighborhood gentrified, Maria added top-shelf whiskeys and craft beers, but keeps things simple and friendly as a rare true neighborhood bar that has stayed just that as the decades passed. The only change was the awning: Maria got tired of people asking what “Karczma” meant and had the awning remade.

So today — some 75 years later — it is the Whirlaway Lounge once more; like the racehorse for which it was named, a little erratic, always high-spirited, and still a winner.

Weegee's Lounge

3659 W Armitage Ave, Chicago, IL 60647

The vibe may be as 1930s as the noir snaps that adorn the walls (shot by Arthur Fellig, the famed New York photojournalist known as Weegee) but this bar has booze in its primordial DNA. Built as a tavern in 1905, only Prohibition made it skip a beat; otherwise, folks have been imbibing here for more than a century. Bar owners came and went (memorably, in 1960, when one owner’s widow put up a sign “closed for death in the family” the bar was promptly burglarized).

Over the decades, it had many names (with just a brief break during prohibition). In the 1980s it was the Chris-Walton Inn, complete with disco balls and poker machines. In 2006, new owners transformed what had been a typical Polish dive into a prescient craft cocktail lounge right before the trend began. Blow ups of vintage Weegee photographs and a black and white photo booth were added and the vintage elements were burnished into the high gloss of a golden age movie set. And check out the patio -- a neighborhood favorite!

The latest owner, Jeff Hoffman, who also owns The Village Tap in Roscoe Village, took over the building earlier this year, and wisely decided not to break the chain. As that widow from 1960 would say, it’s best to keep a good thing going.

O's Tap

2044 N Western Ave, Chicago, IL 60647

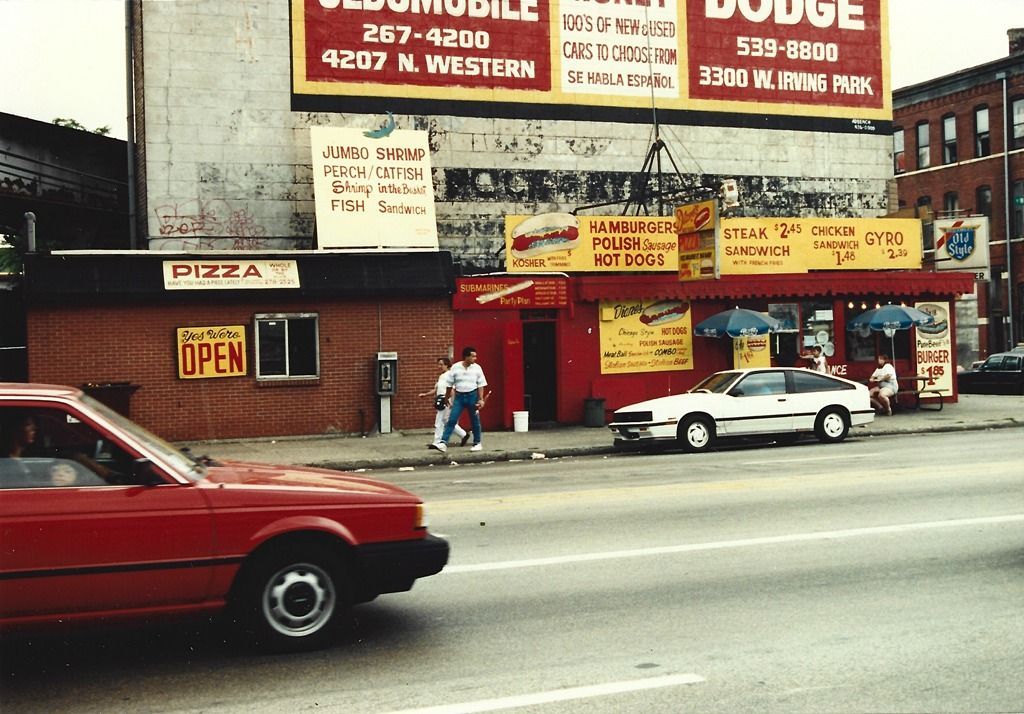

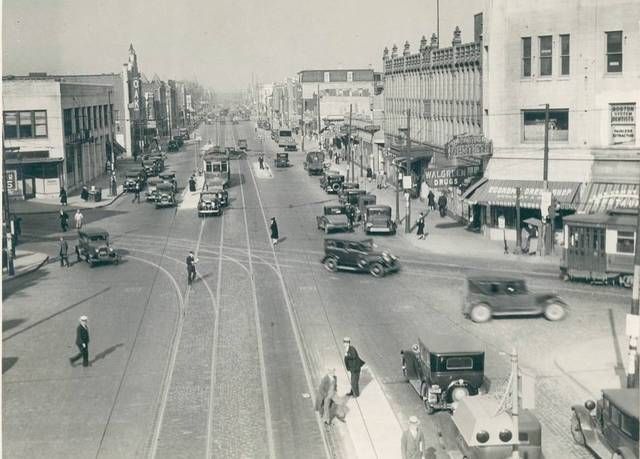

Western and Milwaukee is a busy corner in terms of traffic and turnover. The 1910 Moorish vaudeville house that was the Oak Theater was torn down in 1995 after incarnations as an adult theater and a music venue. But even if the porno palace has since gone condo, a few venerable landmarks remain — some showy, like Margie’s Candies, and some hidden, like the little bar at 2044 N. Western. Built around 1889, the original owners of the building were the family of a streetcar conductor who likely worked at the nearby cable car barn at 2555 W. Armitage.

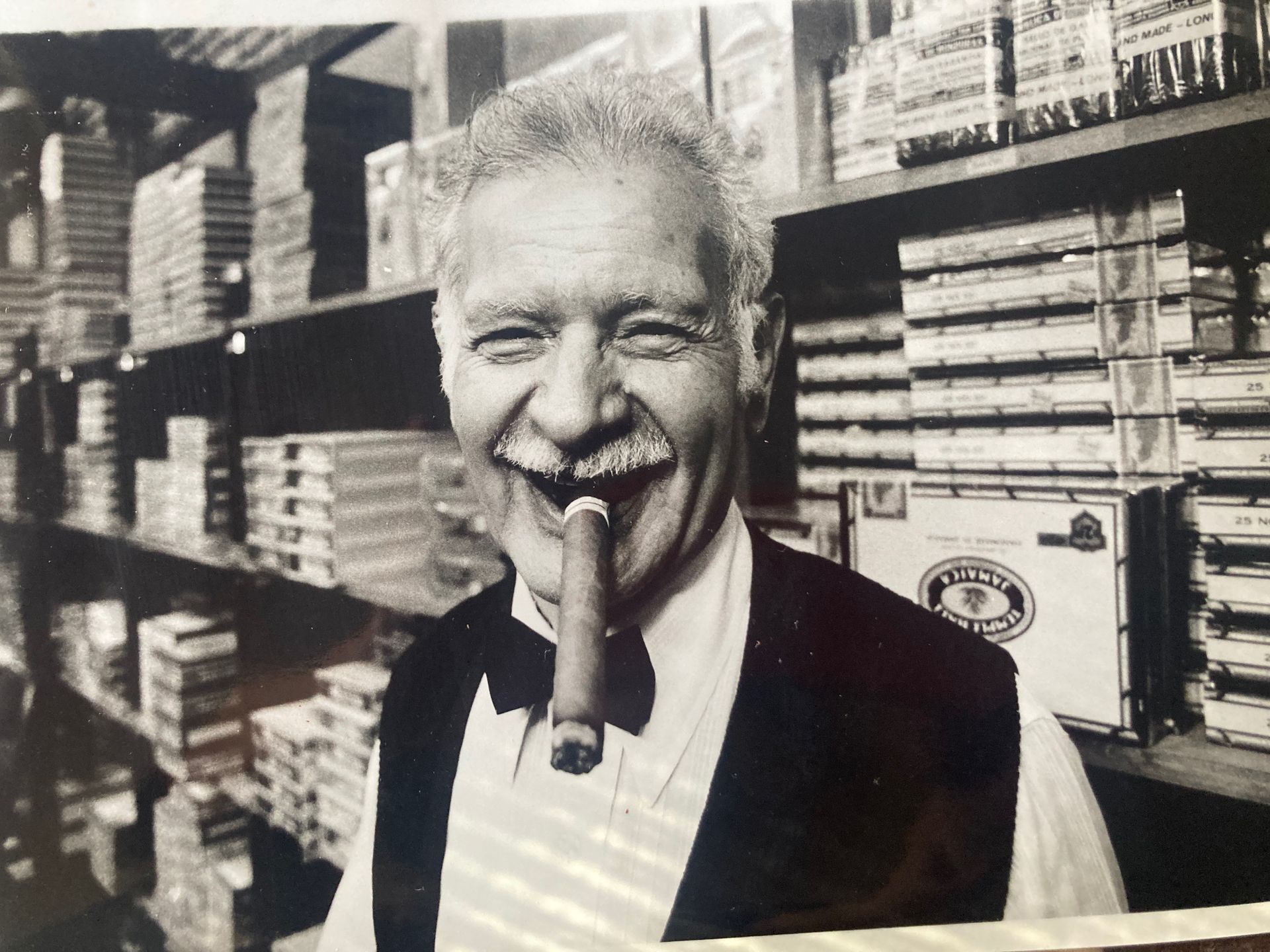

When Walter Josephine Koslowski opened a store on the first floor, the space began its Polish legacy. In 1946, Ted Szczepaniak was operating a tavern there, and it became the Whistlestop by 1949, owned by Raymond Strobot. In 1951, Strobot, who lived in back of the business, shot a burglar he caught looting the bar, wounding him in the arm. The shooting made the papers, but it didn’t seem to deter others. On April 13, 1953, Strobot made the front page of the Chicago Tribune; he was interviewed in his hospital bed after an exchange of gunfire with yet another intruder. Three shots went into Strobot, and the burglar succumbed to his injuries in what the coroner ruled was a justifiable homicide. In 1965, the Whistlestop was bought by cigar aficionado Harry Hacker, who dubbed it Harry’s Place and ran it for almost 20 years before leaving to run the Old Chicago Smoke Shop on North Clark. There, he became known as “Mr. Cigar” for his advocacy and expertise — a nickname used in his obituary after a heart attack in 1987.

In 1985, the Milkowski family bought the bar. Although there was no name on the rather forbidding front, it was known as “Irene’s Place” for the owner’s aunt, a beloved bartender. It was the kind of place, one patron recalls, where the main décor was darkness: “The only light was from the beer cooler and the beer sign. People would open the door and look in — and back right out.” Irene and her loyal regulars largely preferred it that way.

Around 2005, Jimmy Ostrowski — a chemical engineer nicknamed “Jimmy O” for his hard-to-pronounce Polish surname — bought the building. It was supposed to be an investment, but he moved in the next day. Ostrowski spent much of his corporate life traveling the world to supervise chemical recycling projects. Whenever he returned, he’d throw his suitcase on the landing and go straight to the bar downstairs. Irene’s became his basement bar, and even the most insular regulars became his friends.

In 2014, Irene fell and broke a hip at age 87. The bar closed. Ostrowski didn’t want to lose his basement bar and buddies, so he bought it. Ostrowski decided to share what had largely been a secret, no-name club with the world. He started hosting bands and letting artists exhibit.

Every year, he orchestrates one of the biggest hauls for Toys for Tots and regularly hosts birthday celebrations, bridal showers and cookouts. The bunker-like façade got a makeover, with a wide, welcoming open window. Ostrowski added a patio that grew to envelop the back yard next door; he now owns that building, as well. He installed a koi pond bar in the back, but left the vintage Brunswick bar and original tin ceiling inside intact.

As for the classic Old Style sign, it finally got a name below it: O’s Tap. O stands for Ostrowski, of course, but the staff rarely answers the inevitable question straight. You might be told that the O stands for Obama or Bill O’Reilly, depending on which way they think you vote. Or they might throw out any O word that comes to mind — maybe “old school” for the cash-only policy. But for the longtime regulars and first-timers alike, O might just stand for “Our Place.”

Logan Arcade

2410 W Fullerton Ave, Chicago, IL 60647

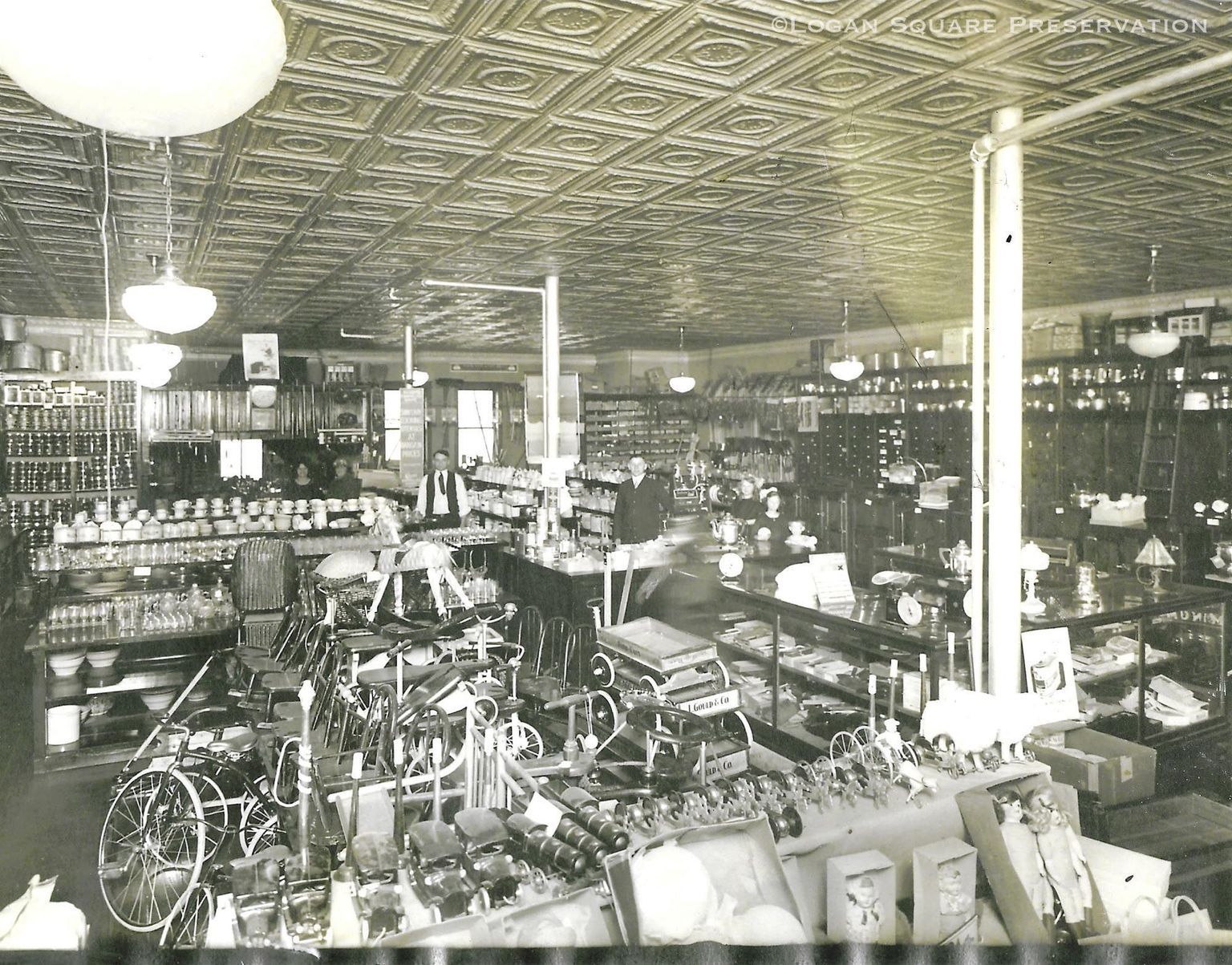

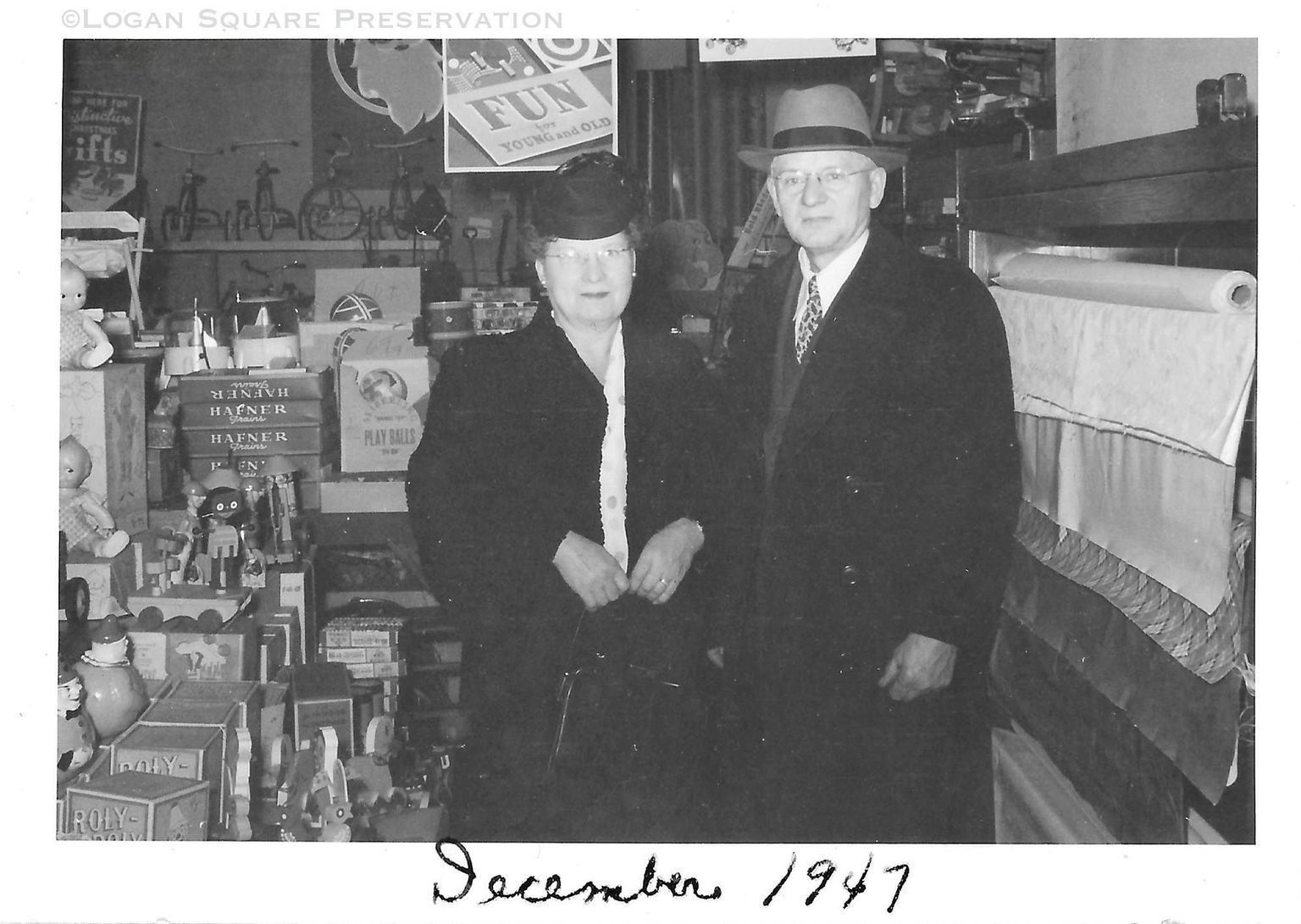

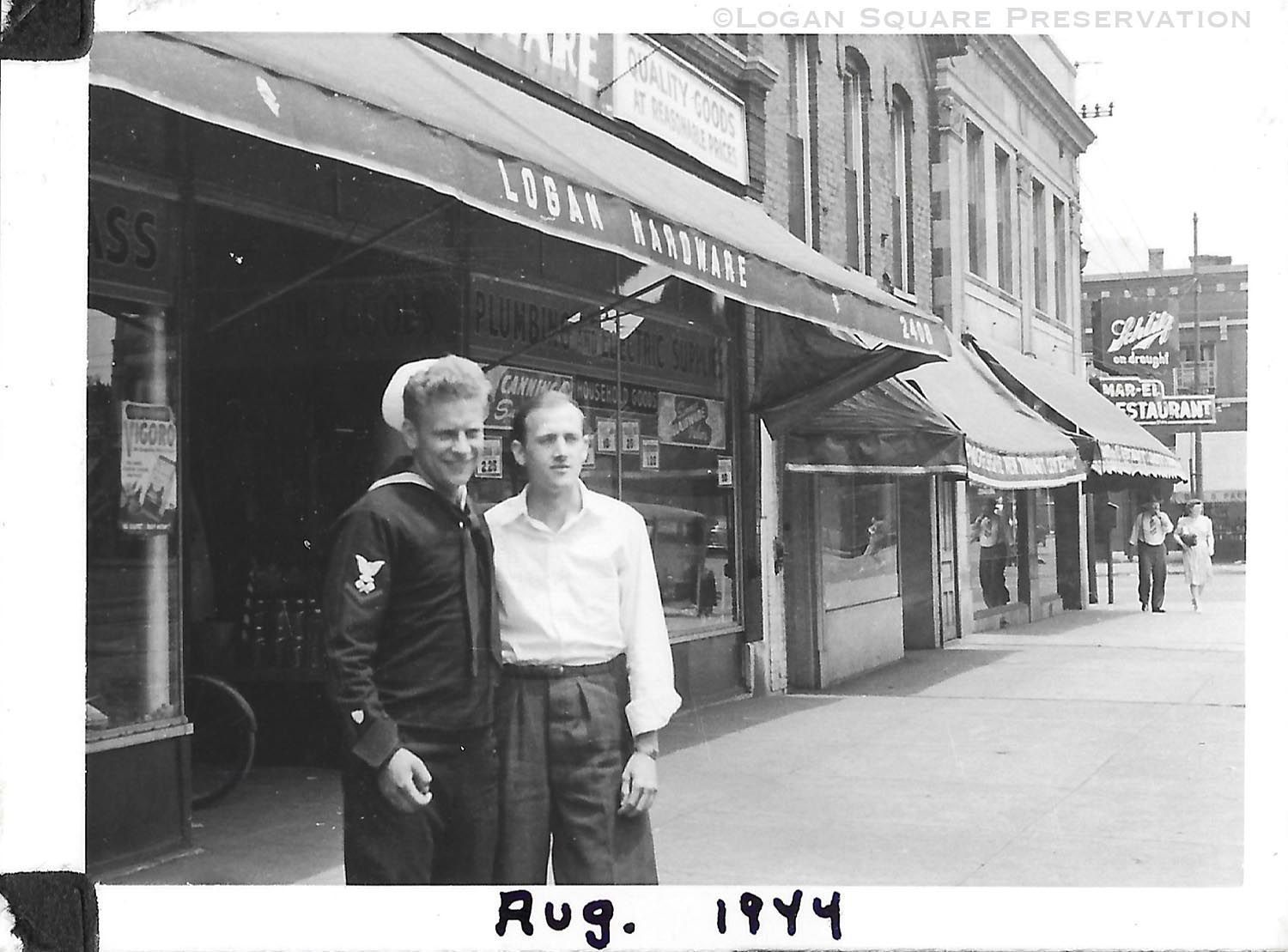

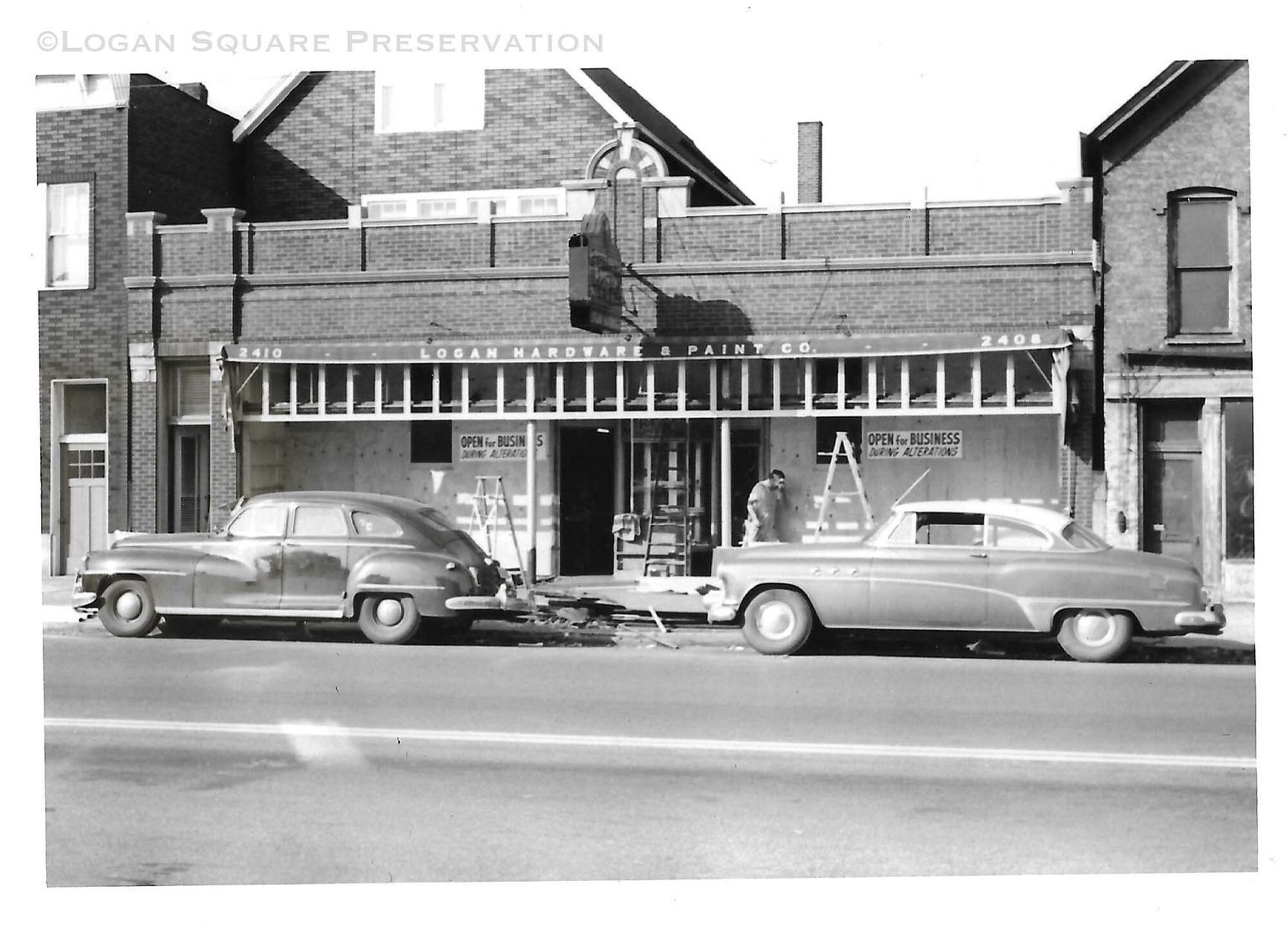

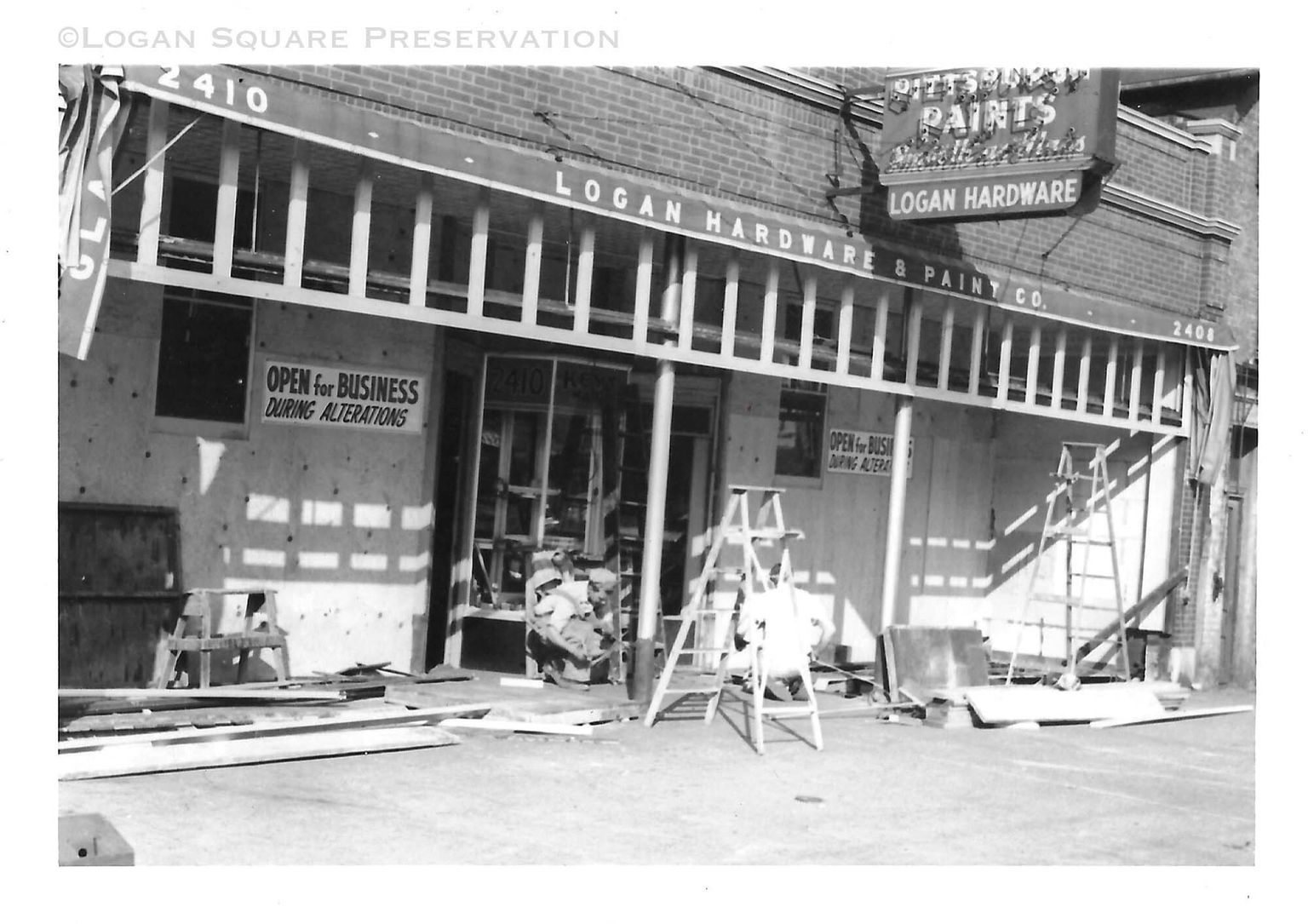

For 100 years, there has been something about 2410 W. Fullerton that has spoken to a special kind of independent entrepreneur — something that said, “Yes, no matter what the odds, you can make it happen here.” That was the story for the Kosiba family, who occupied the building and ran their hardware store here from 1922–1997, and it’s still the case for Jim Zespy, who made his record store-turned arcade-turned bar a reality here.

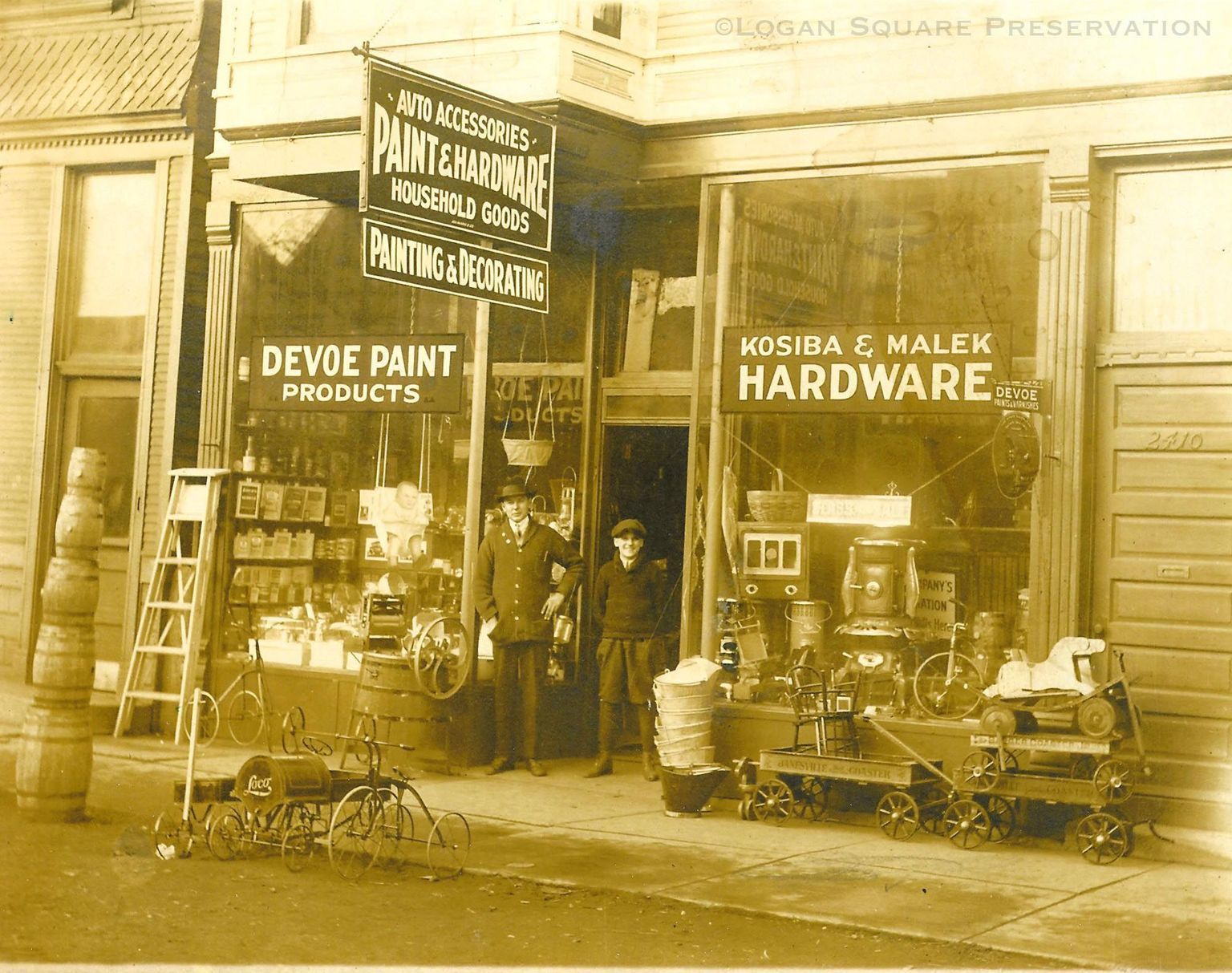

Built in in the late 1800s, the building was originally one of the modest two-story frame hybrids still so common in Chicago – a small storefront ideal for a dog walker, carry-out, or salon, with an owner’s apartment above. Polish immigrant Anton Kosiba saw the building in 1920; he had been renting a similar house a few blocks away for his family and his small grocery and was looking to expand both.

He also saw something that still gets developers excited today — an empty lot next door. He would buy them both, and in 1922 begin building the brick storefront you can still glimpse behind the 1950s façade.

More Than Hardware

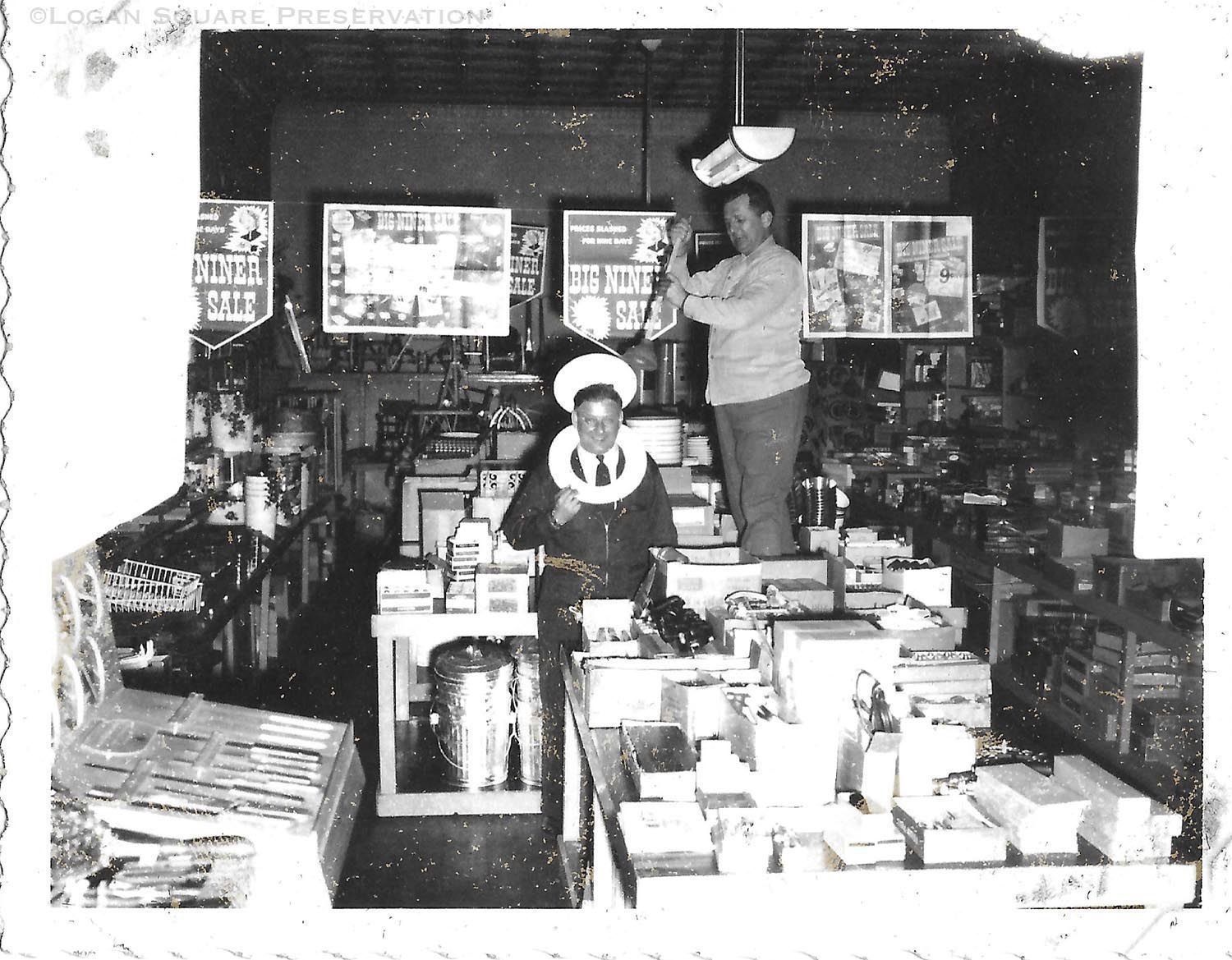

While for most of its life, the storefront has been known as Logan Hardware, the term has been fluid. Hardware meant everything except soft goods and food in the 1920s, and Kosiba family photos show a store crowded with teapots, dishes, sewing machines and toys — wagons, rocking horses, kiddie cars, dolls.

Ironically, considering what the hardware store would become, pinball was illegal during much of Logan Hardware’s history. Thought to be a gambling device and a source of moral decay, debate raged over whether the machines were a game of chance or of skill; adding flippers helped the skill argument, but didn’t convince police. The Kosibas witnessed raids on neighbors such as the Bob Inn, where pinball machines were confiscated and the owners arrested.

In spite of the fact that Chicago was the home of nearly all major pinball manufacturers and distributors including Gottlieb, Bally, and Williams-Stern — “Chicago was to pinball what Detroit was to cars,” Zespy says — crackdowns began in 1937 and peaked in the ’40s and ’50s before the ban was overturned in 1977.

Logan Hardware Today

The unique space — now more arcade-with-a-bar than bar-with-an-arcade — has a rotating collection of rare vintage pinball and arcade games. Zespy hoards original parts to keep the games not only in perfect working order but in original working order. The Logan Arcade and bar has been a hit, especially with pinball aficionados who have repeatedly voted it the best place in the nation to play. It managed to survive the pandemic and 18 months of closure. Throughout, Zespy has stayed close to the Kosibas, and in a recent conversation with Larry for this Meetup, asked for a few words in Polish that would be appropriate. “Sto lat,” Larry said. “That’s what they sing to me on my birthday: ‘May you live 100 years – 100 years – and 100 years more.’”

The Double

3545 W Fullerton Ave, Chicago, IL 60647

From a 1911 saloon to a rough-and- tumble tavern in the ‘60s where a three-man fight over a woman that left just two men standing, this neighborhood spot has seen some action. But the vibe started to change at what was once the Fullerton-Drake Lounge. By the 2000s the Polish tavern had evolved into a hipster coffee shop called Hotti Biscotti. Weekly avant-garde jazz jam sessions and a liquor license followed, along with ads in the freebie give-away paper "Logan Square Free Press."

But its double life officially began at the end of 2010 when the current owner dug up the ceramic covering the old terrazzo, repaired the back bar and tin ceiling, and installed (for the first time) a modern draft beer system. Its signage promises to welcome everyone in the diverse neighborhood: "social climbers and punk rockers...meatheads and hipsters...white collar / no collar."

As the two-faces of The Double Tavern’s sign implies -- the best of old meets new.

Fireside Bowl

2646 W Fullerton Ave, Chicago, IL 60647

It’s not just a rare vintage (as opposed to retro) old-school bowling alley, right down to its antiquated scoring system, Fireside Bowl is the perfect Chicago backdrop. You might see one of the local tv series shooting here (“Chicago Fire,” “Chicago PD”) or the occasional movie (think “Widows,” or Jennifer Aniston’s “The Break-Up”). Its high gloss Art Deco ceramic brick facade is a favorite of local artists -- it's been memorialized countless times.

Before it was a bowling alley, it was an auto garage with apartments above, built by the Mesce family. Since cars were new and expensive, wealthier people stored their cars at the garage and would show up to call for their cars, which were parked and painstakingly maintained in this early valet system.

In 1941, at the height of the bowling craze, the garage, which had been bought by Henry Sophie, was remodeled into a 12-lane bowling alley, which was expanded to 16 lanes in 1956. Ten years later, Sophie, who had bought a Mt. Prospect golf course, sold the business to Rich Lapinsk, and it’s been in that family ever since.

Fireside weathered a drop in bowling popularity in the 1990s by becoming a premier punk venue for bands like with Fallout Boys and My Chemical Romance. In 1999, rocked by noise complaints from neighbors and the threat of eminent domain to expand Haas Park, Fireside pivoted back to bowling. In 2004 it was renovated, but kept all its classic charm. So even if you’re not league material, stop in, check out the original attached bar, crammed with vintage liquor memorabilia and enjoy being part of a genuine tourist attraction (even John Hamm stopped in earlier this year to check it out). You’re in good company.